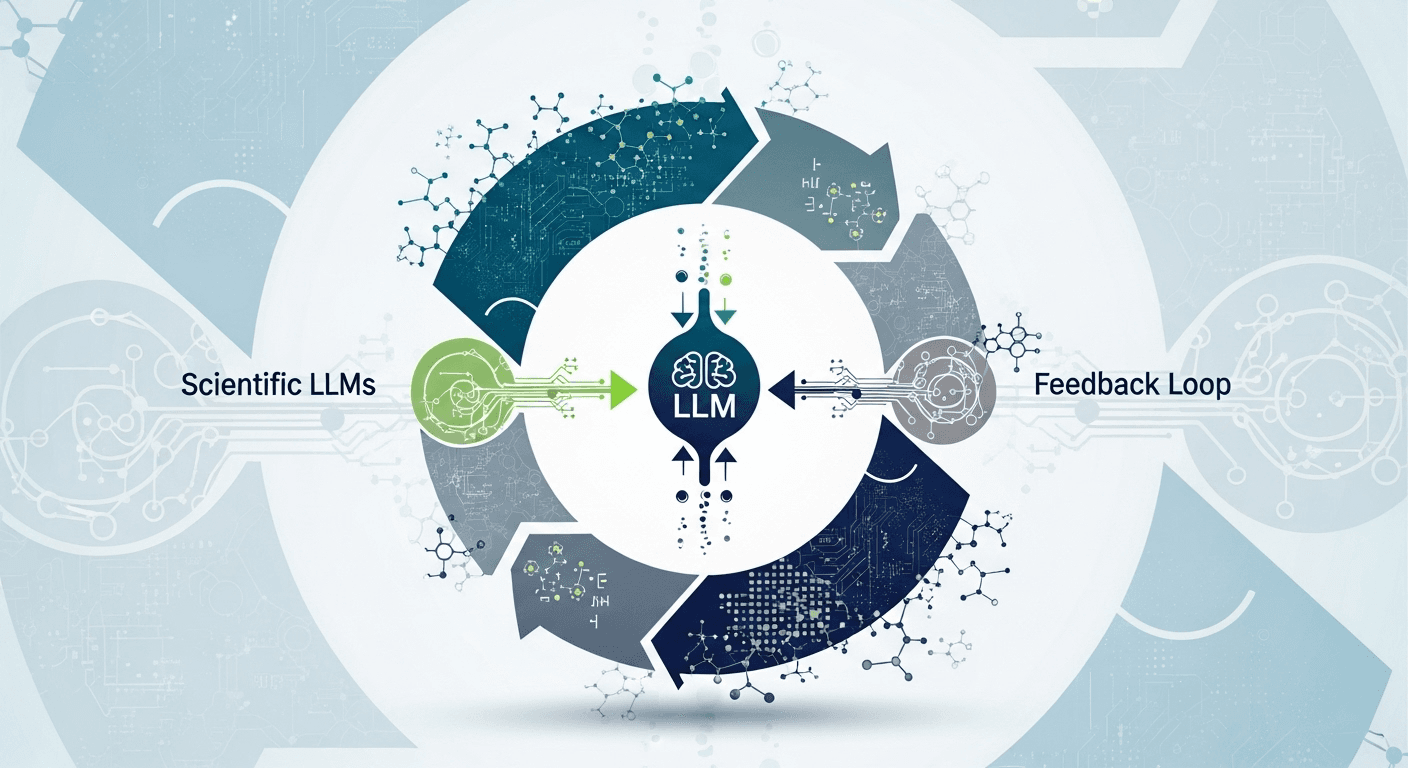

Scientific Large Language Models Explained: A Practical Survey and Feedback Loop to Overcome Data Barriers

Scientific Large Language Models Explained: A Practical Survey and Feedback Loop to Overcome Data Barriers

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly utilized to read academic papers, summarize findings, propose hypotheses, and assist in planning experiments. However, scientific domains face unique challenges, including limited high-quality data, rigorous reproducibility standards, and minimal tolerance for inaccuracies. This article provides a comprehensive overview of scientific LLMs and outlines a feedback-loop strategy to overcome the data barriers that often hinder their performance and trustworthiness.

Understanding Scientific LLMs

Scientific LLMs are specialized models designed for tasks in science and engineering, including reading scholarly articles, answering domain-specific questions, extracting structured information, drafting methods sections, generating analysis code, and proposing as well as critiquing hypotheses. Some are general-purpose LLMs that incorporate additional tools and retrieval capabilities, while others are domain-specific models that have been pre-trained or fine-tuned on scientific literature and laboratory texts.

Importance: General chat models can sound fluent but may produce incorrect information, especially in technical areas. Scientific LLMs aim to enhance accuracy, citation integrity, and task efficacy by focusing on the content, tasks, and workflows typical in research and R&D.

Challenges Facing General LLMs in Scientific Domains

- Data scarcity and paywalls: Much valuable content is inaccessible due to paywalls, and while open-access databases exist, their coverage varies by field.

- Precision and verifiability: Claims require citations, data must align with original sources, and methods ought to be reproducible; even minor mistakes can mislead entire projects.

- Jargon and extensive contexts: Scientific writing often contains specialized terminology and may extend over lengthy documents that include figures, equations, and references.

- Safety and ethics: Incorrect suggestions in critical areas like medicine can have severe real-world implications.

These challenges highlight the need for domain-specific models and tool-enhanced workflows tailored for scientific inquiries.

A Brief Survey of Scientific LLMs and Tools

The following models and methods represent significant developments in the field. This is not an exhaustive list but showcases important directions that have influenced scientific LLMs.

Domain-Pretrained and Fine-Tuned Models

- SciBERT (2019): A BERT variant trained on diverse scientific texts; demonstrates improved outcomes in scientific NLP tasks such as named entity recognition and paper classification [Beltagy et al., 2019].

- BioBERT (2019): A BERT model tailored for biomedical texts, showcasing enhanced performance in biomedical named entity recognition, relation extraction, and question answering [Lee et al., 2019].

- PubMedBERT (2021): Developed from scratch using PubMed data; achieves strong results by eliminating domain mismatches in biomedical assessments [Gu et al., 2021].

- BioGPT (2023): A generative transformer designed for biomedical text generation and mining tasks [Luo et al., 2023].

- ClinicalBERT (2019): Adapted for clinical notes, focusing on electronic health record-centric tasks such as concept extraction and mortality prediction [Alsentzer et al., 2019].

- Galactica (2022): A transformer educated on scientific literature, code, and specialized knowledge bases; noted for its citation-aware generation, alongside discussions on reliability [Taylor et al., 2022].

- Med-PaLM/Med-PaLM 2 (2023): Instruction-tuned models for medical question answering that excel in expert assessments and provide safety-tuned outputs [Singhal et al., 2023].

General LLMs with Scientific Workflows

- Tool-Augmented Reasoning: Methods like ReAct merge chain-of-thought reasoning with tool usage, permitting models to search, retrieve, and compute as they reason [Yao et al., 2023]. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) grounds responses in source documents [Lewis et al., 2020].

- Coding for Science: Models such as Code Llama and AlphaCode focus on scientific programming, demonstrating proficiency in coding challenges and benchmarks [Roziere et al., 2023], [Li et al., 2022].

- Research Assistants: Tools like Elicit and Consensus facilitate retrieval, summarization, and paper organization workflows, enhancing literature reviews [Elicit], [Consensus].

Datasets and Benchmarks for Scientific Evaluation

- PubMedQA and BioASQ: Datasets focused on biomedical question answering that emphasize evidence-backed responses [PubMedQA], [BioASQ].

- ScienceQA: A multimodal dataset incorporating science questions that necessitate the use of diagrams and reasoning [Lu et al., 2022].

- MMLU: A broad knowledge benchmark featuring scientific categories, commonly employed to assess LLMs [Hendrycks et al., 2021].

- SciBench: A challenging evaluation platform for scientific reasoning and problem-solving [Guo et al., 2023].

The Data Barrier: Understanding Its Nature and Persistence

The data barrier refers to a situation where the quality of models is more constrained by access to high-quality, licensed, and current domain data than by model size itself. In scientific contexts, this manifests in various ways:

- Access Limitations: Many academic journals are not open access. Responsible training usually necessitates permission or licensing, even with fair-use exemptions.

- Quality and Bias: Scientific texts may include retractions, conflicting findings, and biased samples. Without careful curation, errors can be exacerbated by models.

- Knowledge Fragmentation: Information is dispersed across articles, supplementary materials, datasets, code repositories, and preprints.

- Evaluation Obstacles: There is a lack of standardized methods to effectively measure factual accuracy, citation integrity, and genuine scientific utility.

While open resources like PubMed and PubMed Central provide access to biomedical abstracts and many full texts [NIH PubMed], [PMC]; arXiv covers numerous preprints [arXiv]; and platforms like OpenAlex and Semantic Scholar assist with metadata and discovery [OpenAlex], [Semantic Scholar], these resources alone are insufficient. Modern scientific LLM systems necessitate a feedback loop that transforms access, verification, and expert feedback into systematic improvements over time.

A Feedback-Loop Blueprint to Surpass the Data Barrier

Relying solely on a one-size-fits-all model is inadequate. High-stakes scientific endeavors benefit from a system that continually grounds, tests, and evolves. Below is a practical framework that you can implement today.

1. Curate and Govern the Knowledge Base

- Ingest vetted sources: integrate open-access articles (PMC), preprints (arXiv), datasets, lab notebooks, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and internal reports with established permissions.

- Normalize text: convert PDFs to structured text, extract tables and captions, and resolve references to DOIs and PubMed IDs.

- Track Provenance: Ensure every piece of information includes its origin (URL, DOI, version) and date of access.

- Continuous Updates: Schedule regular re-ingestion and re-indexing to include new papers and any retractions.

2. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Grounding

- Implement dense retrieval methods (e.g., DPR) or hybrid search to pull evidence prior to formulating answers [Karpukhin et al., 2020].

- Use RAG prompt patterns: supply the model with top passages and require direct quotations or citations [Lewis et al., 2020].

- Long contexts can be beneficial but should not replace retrieval methods; mixed strategies tend to be more effective, particularly for synthesizing multiple documents.

3. Verifiers and Critics for Automatic Checks

- Citation Resolvers: Ensure every reference resolves to a valid DOI or PubMed entry; flag any non-resolving citations.

- Fact-Checking through Retrieval: Requery essential claims and compare them to original texts; engage a secondary model to highlight discrepancies.

- Math and Code Execution: Direct equations to a computational algebra system (CAS) or Python; execute model-generated code in a controlled environment and compare results to stated claims.

- Style and Safety Checks: Verify that language avoids overstatement and complies with domain safety guidelines.

4. Human-in-the-Loop Reviews

- Engage subject matter experts to review high-impact answers and experimental designs.

- Utilize structured evaluation rubrics: assess evidence adequacy, correctness, handling of uncertainties, and reproducibility.

- Gather preferences and mistake annotations to refine the model through instruction tuning or preference optimization [Ouyang et al., 2022], [Bai et al., 2022].

5. Active Learning and Synthetic Data (With Precautions)

- Allow the model to flag low-confidence queries and seek labels; focus expert efforts where the model can learn most [Settles, 2012].

- Generate synthetic question and answer pairs along with rationales from your curated dataset; retain only those that pass verification and human review.

- Employ contrastive examples: gather instances where the model performed poorly and incorporate these into further training.

6. Closing the Loop with Experimental Data (When Applicable)

In laboratory-centered fields, link the LLM to automation or simulation environments. The model can propose experiments, the lab can execute them, and results can feed back into the knowledge base and training set. This concept underlies the notion of self-driving labs and autonomous discovery workflows [Reid et al., 2020].

7. Measurement: Evaluate What Matters

- Task Metrics: Benchmark on domain-specific tasks (BioASQ, PubMedQA, ScienceQA, SciBench) with rigorous scoring for citation accuracy and factual integrity.

- Process Metrics: Monitor citation resolution rates, verification pass rates, and expert approval rates.

- Outcome Metrics: Assess time spent on literature reviews, the number of corrected errors pre-publication, and improvements in experimental hit rates.

Key Insight: Instead of aiming for a flawless model, create a virtuous cycle where retrieval, verification, and expert feedback continuously enhance quality and trust.

Real-World Applications of the Feedback Loop

Example 1: Literature Triage for a New Protein Target

- Index open-access articles and preprints discussing the target and related pathways.

- Instruct the LLM to summarize evidence linking the target to related diseases, incorporating inline citations.

- Run verifiers: ensure all DOIs resolve correctly and that cited claims correspond with the source material.

- Have a scientist review the leading claims, categorize them (supporting vs. conflicting evidence), and flag any retracted items.

- Fine-tune the model on this annotated dataset; repeat the process weekly as new articles are published.

Outcome: Accelerated and more reliable reviews, resulting in a growing private dataset of high-quality, labeled evidence.

Example 2: Materials Discovery through a Self-Driving Loop

- Initialize the knowledge base with open crystallography data, synthesis protocols, and property tables.

- Utilize the LLM along with a Bayesian optimizer to suggest candidate compositions and synthesis parameters.

- Execute experiments using a robotic platform; automatically ingest results along with comprehensive metadata.

- Retrain the proposer using active learning to concentrate on promising areas of experimentation.

- Document uncertainty and rationales for each recommendation; ensure verification prior to scale-up.

Outcome: Enhanced hit rates and a continually evolving dataset directly linked to experimental results.

Key Design Decisions Impacting Scientific LLMs

Grounding and Citations

- Always provide sources. Require the model to cite information both inline and in a references section. Penalize non-resolving citations during training and evaluations.

- Favor exact quotes for critical facts and figures. While summaries are valuable, allow readers to quickly verify key claims.

Uncertainty and Calibration

- Encourage the model to express uncertainty. Calibrated confidence scores can help prioritize human review.

- Value abstaining over delivering incorrect confident responses. In scientific discourse, indicating “insufficient evidence” is a strength.

Prompting and Tool Use

- Employ step-by-step prompting judiciously. Chain-of-thought techniques can enhance reasoning but should complement verification processes [Wei et al., 2022].

- Integrate tools: literature searches, knowledge graph inquiries, calculators, and code execution can significantly minimize inaccuracies.

Privacy, Licensing, and Ethics

- Adhere to licenses and privacy regulations. Separate proprietary data and ensure proper audit trails are maintained.

- For clinical applications, comply with medical device regulations and data protection standards. Involve human oversight for any decisions affecting patients.

Evolving Trends in the Field

- More Specialized Models: Domain-adapted models with retrieval capabilities are increasingly competitive with larger general models for targeted tasks, often at a lower cost with enhanced controllability.

- Multi-Agent Systems: Specialized agents (retriever, resolver, critic) collaborate to mitigate single-model failure modes, allowing for richer verification processes.

- Extended Contexts and Structured Memory: As context windows expand, teams are combining them with knowledge graphs and vector stores to optimize reliability and cost-effectiveness.

- Closed-Loop Scientific Processes: Integrating with laboratory robotics and simulation systems is progressing from initial demonstrations to full-scale production in fields such as materials and chemistry, bridging the gap between analysis and application.

Quick-Start Guide

- Define the Scope: Determine which tasks, subfields, and associated risks are relevant.

- Compile an Open Corpus: Utilize PMC, arXiv, specialized datasets, and your own documents, ensuring proper permissions are in place.

- Develop a RAG Pipeline: Implement hybrid search, precise chunking, and citation-integrated prompts.

- Add Verifiers: Incorporate measures for citation resolution, fact-checking, code execution, and safety reviews.

- Close the Loop: Incorporate expert evaluations, collect preferences, tune the model, and assess progress continually.

- Scale Responsibly: Keep track of costs, data licensing, and safety outcomes as usage increases.

Conclusion

Scientific LLMs can provide tremendous value when they are designed not just to be smart, but to be grounded, verifiable, and continually evolving. The pathway ahead is through a feedback loop, which entails curating reliable data, retrieving evidence, verifying claims, and integrating insights from both expert feedback and experimental outcomes. This systemic approach enables us to navigate past data barriers and transform language models into trustworthy partners in discovery.

FAQs

What distinguishes scientific LLMs from general LLMs?

Scientific LLMs are specifically trained and evaluated on domain-related texts and tasks, emphasizing grounding in sources and often incorporating retrieval and verification. The objective is to prioritize substance and reproducibility over mere stylistic fluency.

Can scientific LLMs replace human researchers?

No. They serve as aids that expedite the reading, synthesis, and hypothesis development processes. Human expertise is essential for judgment, context, ethics, and oversight, especially in high-stakes situations.

How can hallucinations in scientific responses be minimized?

Ground claims through retrieval, mandate citations, introduce automated checks for facts and calculations, and incorporate human evaluations for critical outputs. Penalizing ungrounded statements in the training phase is also crucial.

Are open-source models sufficient for serious scientific work?

Often, yes, particularly when paired with strong retrieval and verification processes. Domain-adapted open models frequently outperform larger general models on specific tasks, representing a cost-effective and controlled option.

What about sensitive or proprietary data?

Maintain it within a controlled framework with stringent governance. Employ on-premises or private deployment strategies, ensuring detailed provenance and audit trails.

Sources

- Beltagy I, Lo K, Cohan A. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.10676

- Lee J et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08746

- Gu Y et al. Domain-Specific Language Model Pretraining for Biomedical Natural Language Processing (PubMedBERT). https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.15779

- Luo R et al. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.10341

- Alsentzer E et al. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.05342

- Taylor R et al. Galactica: A Large Language Model for Science. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.09085

- Singhal K et al. Towards expert-level medical question answering with large language models (Med-PaLM 2). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06291-2

- Yao S et al. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.03629

- Lewis P et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.11401

- Karpukhin V et al. Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.04906

- Roziere B et al. Code Llama: Open Foundation Models for Code. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.12950

- Li Y et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05637-4

- Lu P et al. Learn to Explain: Multimodal Reasoning via Thought Chains for Science Question Answering (ScienceQA). https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.14350

- Hendrycks D et al. Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding (MMLU). https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03300

- Guo Z et al. SciBench: Evaluating college-level scientific problem-solving ability of LLMs. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.10635

- NIH PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

- arXiv. https://arxiv.org/

- OpenAlex. https://openalex.org/

- Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/

- Settles B. Active Learning. https://burrsettles.com/pub/settles.activelearning.pdf

- Ouyang L et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155

- Bai Y et al. Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI Feedback. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.08073

- Reid JP et al. Autonomous discovery in the chemical sciences. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41570-020-00207-2

- Wei J et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903

- Elicit. https://elicit.com/

- Consensus. https://consensus.app/

Thank You for Reading this Blog and See You Soon! 🙏 👋

Let's connect 🚀

Latest Insights

Deep dives into AI, Engineering, and the Future of Tech.

I Tried 5 AI Browsers So You Don’t Have To: Here’s What Actually Works in 2025

I explored 5 AI browsers—Chrome Gemini, Edge Copilot, ChatGPT Atlas, Comet, and Dia—to find out what works. Here are insights, advantages, and safety recommendations.

Read Article